Layers of sacred reflections

Centuries of artistry turned the Mogao Caves into silent witnesses of China's unfolding cultural and political saga, Zhao Xu reports in Dunhuang, Gansu.

Ushering in a golden age

The Mogao Caves do not lack grandeur — the tallest Buddha soars 35.5 meters, and 492 of the 735 surviving caves feature painted walls and sculptures. Even the modest Library Cave contains sparse wall paintings.

According to Zhong, emperors of China's short-lived Sui Dynasty (581-618) — which reunified the country after a long period of fragmentation — sought to standardize Buddhist practice and imagery. Unsurprisingly, they favored grandiosity, ushering in a golden age of opulence in Dunhuang mural art that continued to flourish well into the Tang Dynasty.

The influence of Indian Buddhism is on view in Dunhuang — the grotto caves themselves are rooted in the design of Chaitya Hall, a Buddhist prayer hall in ancient India typically carved into hillsides. These halls featured barrel-vaulted roofs visually supported by ribbed arches resembling wooden beams, and a stupa at one end for circumambulation — walking around the stupa in reverence, explains Zhong.

"All of these elements were preserved in Dunhuang. On the other hand, the imprint of Chinese culture is unmistakable. Among other details, the transformed visages, physiques and attire of the statues reflect the growing confidence with which Chinese artists and artisans expressed their own vision of the Buddha and his realm — ultimately making Dunhuang an emphatic footnote in the narrative of Chinese cultural and political history."

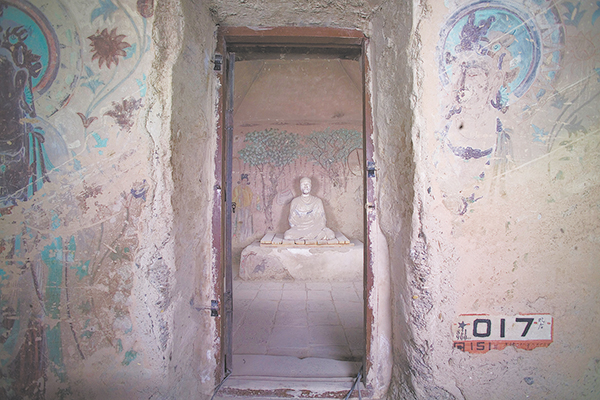

With all that said, it is often in the quieter corners of the caves that one is reminded of what compelled a monk named Yuezun to carve what is believed to be the very first Buddhist cave in 366, which would later become the Mogao Caves.

"Legend has it that Yuezun saw a nearby mountain bathed in a golden glow and believed it to be a divine calling from the Buddha," says Zhong.

"He responded by taking his chisel and carving into the sandstone cliff, creating what is believed to be the very first Buddhist cave in Dunhuang. Though we cannot locate it today, that cave was likely a small meditation cave — just large enough for one person to sit, with a height that accommodated only a seated figure."

Today, similar meditation caves can still be found in the Mogao Caves often tucked into the side or back walls of larger caves, their view sometimes obscured by stupas built inside for circumambulation. According to Zhong, a meditative monk would spend months in such a cave, with food brought in to sustain them.

In the 2nd century BC, upon being made a commandery by a Han emperor, Dunhuang, which in Chinese implies greatness and magnificence, was named.

When asked about the origin of the name "Mogao", Zhong says: "We don't know for certain, but some believe this place was once called Mogao village. Other researchers have pointed to the literal meaning of the term 'Mogao', which can be translated as 'no higher (than)'.

"There's no merit higher or greater than creating a space devoted to the worship of the Buddha — that could be what it meant."

Ma Jingna contributed to this story.