Voyages for a new world order

Exhibition highlights Zheng He's extraordinary journeys, Zhao Xu reports.

These expeditions laid the groundwork for centuries of trade and diplomacy, leaving behind a trail of cultural relics scattered along the shores of history.

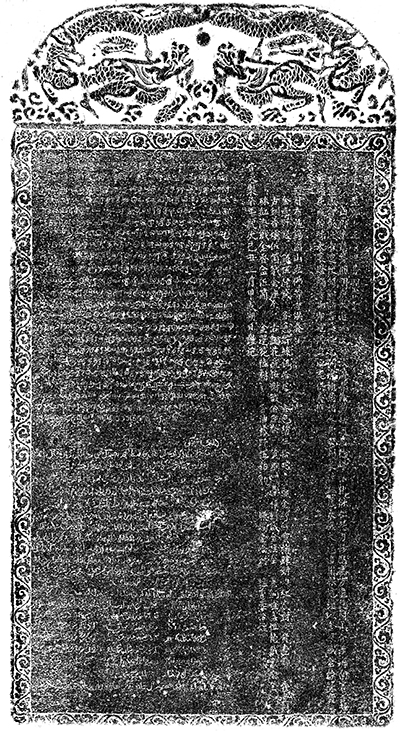

At its height, Zheng's fleet included nearly 300 ships and a crew of 20,000, among them a large medical corps. A stone epitaph rubbing of one of the doctors who served in the fleet is featured in the exhibition.

"Although the exact dimensions of Zheng's legendary wooden vessels remain debated, there is no doubt that his fleet was designed to awe," says Gao.

"However, the goal was never conquest."

According to the curator, bu zheng, or not to conquer, was a clearly articulated state policy established by the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming Dynasty.

"One of the core beliefs," he explains, "was that the Confucian ideals enshrined by Ming society would, in themselves, attract neighboring countries to align culturally and ideologically with China."

Guided by this principle — and wary that open maritime trade might disrupt China's agrarian society and threaten imperial authority — the early Ming rulers tightly controlled overseas commerce. Only the tributary trade system was allowed.

Under this system, foreign missions presented valuable tribute to the Ming court and, in return, received generous imperial gifts, official recognition, and trading rights. The rewards often surpassed the tribute's value, making the system economically appealing.

Carrying overseas highly coveted Chinese goods such as silk and porcelain, Zheng returned not only with spices and precious gemstones — some of which were later crafted into elaborate accessories found in the tombs of Ming vassal kings and their consorts — but also with dozens of diplomatic envoys and royal representatives from places he had stopped by, including Sri Lanka, where the aforementioned stone stele was found.

Believed to be funded in part by wealth from Zheng's voyages, the Da Bao'en Temple in Nanjing was one of the grandest Buddhist temples of the Ming Dynasty.

Covered in glazed brick, it stood as an architectural marvel before its 19th-century destruction. It was frequently depicted in copperplate prints that circulated in Europe, shaping Western visual imagination and perceptions of imperial China.

Yet, the true talk of the town was the arrival of exotic animals — zebras, lions, leopards, ostriches, and most notably, giraffes — first presented to the Ming court by envoys from Bengala, an ancient kingdom located in what is modern-day Bangladesh, which had likely obtained the creatures from elsewhere.